There’s been plenty of talk about the toxicity of stans towards other stans, towards journalists simply doing their jobs, and towards people who did absolutely nothing. But there’s been little discussion on the toxicity of stans toward their faves.

Part of the reason may be our natural inclination not to have empathy for celebrities who aren’t, you know, dead. Our cynicism towards celebrities seems to be based on the idea that once a person crosses a certain threshold of fame and wealth, they’ve forfeited the right to any human decency. And in the popularity-obsessed era of social media, many people would put their meemaws on the hoe stroll to have an army of obsessed followers (toxic or not).

Nevertheless, we’ve arrived at a point in stan culture where artists might have difficulty distinguishing their stans from their haters and some fans have surpassed being mildly irritating to being the most demoralizing forces in their faves’ lives and careers.

Here are just a few ways that stans have become as toxic to their faves as trolls.

The “We” Syndrome

Stans are always willing to share in the successes of their faves, but they rarely want to share responsibilities for any failures.

It’s always “we got a #1 hit” or “we got another sold-out tour”.

But you rarely hear: “we fell off the charts after one week”, “we sold 50 tickets in a 70,000-seat stadium”, or “we just got busted in the bathroom with cocaine“.

It’s natural to feel that you are part of your fave’s achievements, but some stans don’t seem to understand the difference between being a consumer and being an investor. Investors put large amounts of money into ventures with the hopes of large returns. Stans (consumers) aren’t obligated to contribute anything more than free streams, they risk nothing (except likes and retweets), and they don’t see any financial returns. And yet, many stans have convinced themselves that they are equal partners who should have a legitimate say in their faves’ career and life decisions.

It’s the artist who risks their name and reputation when they release a project and they are always one personal or professional misstep for losing years of built-up goodwill. Stans, however, get to hide safely behind anonymous stan accounts — claiming victory during successes and playing the blame game during flops.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting your fave to be successful, but some fans actually believe that after working for decades to create billion-dollar brands, these artists actually give a damn about stans’ Cashapp-ass Twitter bragging rights.

And if stans were as omnipotent and almighty as they purport to be, then no artist would ever flop. Right?

You Don’t Have To Be An Actual Stan to Have a Stan Account

As stan culture grew, so did the incentives of being in a stan group.

Stan groups became less like fan clubs formed around an artist’s work and personae and more like social clubs where the group’s status and its members hinged on the popularity and current chart success of their faves.

Eventually, the artists themselves became secondary and the end game of stan groups was no longer representing and defending artists, but using that artist’s fame for engagement. For some, stan groups became a way to fellowship with other like-minded fans. For others, it’s a low-risk, high-reward means of making friends on the internet — whether they actually like the artist or not.

The rewards of creating a social life around stan culture far outweigh the risks.

Stan accounts provide the opportunity to hide behind other people’s images and achievements and be sharply critical (and downright vile) without ever having to submit any of your actual self to any judgment. And allows stans to achieve a level of popularity that they probably wouldn’t have gotten with a social media account dedicated to their lives and their accomplishments.

Stans Are More Obsessed With Sales Than Their Faves

Before stan culture, fans could cultivate their tastes in music without a 24-hour obsession with chart stats. Although the idea popularity-based ranking didn’t start on Stan Twitter (we had TRL and 106 and Park), fans could consume content and form opinions without a minute-by-minute fixation on sales or streams.

But as the digital music market gained prominence, so did the prevalence of music analytics. Virtually every platform on which a stan consumes music (i.e. Youtube, Spotify, iTunes, Soundcloud) is attached to a metric, and stans are constantly aware of the current popularity of the music they consume.

The death of pure sales has made things worse

You’d think that the tragic death of pure sales would cause a decline in stan chart obsession, but the decline of actual sales seems to have made stans even fussier in their chart obsessions. Because stan culture is a 24-hour pulse check of our faves’ popularity, it leaves little room for anything less than an instant smash hit. It’s no longer enough to get a Top 10 hit; it has to be #1. And it can’t eventually find its way to #1; it has to debut at #1 and stay longer than Mariah, Lil Nas X, and all Boyz from Boyz II Men.

This obsession with chart performance can quickly turn into restlessness. And if the commercial performance of a record falls short of expectation (or worse, if it outright flops), that restlessness can turn to outright stan resentment towards the artist.

Young Stans vs. Grown Artists

Many younger stans still base their self-worth on how liked and popular they are (even if that popularity means adopting ideas and opinions they don’t believe in). And because being popular is so crucial to them, many stans project their obsession with validation onto their faves.

So when their faves don’t fully exploit their current popularity (or, worse, do things that could make them less popular), some stans take it personally.

Why is my fave not in everyone’s face promoting?

Why is my fave making music that could ostracize a large part of their fanbase?

Why is my fave being nice to a person that Twitter told me not to like?

Why is my fave not neurotically obsessed with being seen and validated by as many people as possible?

That is not to say that commercial success isn’t important or even necessary (our faves didn’t become our faves by bubbling under the Bubbling Under Charts). But if you’ve spent decades building a body of work and achieving a certain level of commercial success, at a certain point, you’ve earned the right to do whatever you want to do.

Many artists reach a place in their careers where they want to create with more meaningful end goals in mind than simply being liked by the largest number of people. But it’s hard to convey the joys of authentic expression to stans whose opinions change as often as Twitter trending topics do. And it’s difficult to explain the importance of creative ownership to stans whose entire online identities are based on other people’s work.

Stans’ Annoying Habit of “Fighting” Toxicity by Spreading It

In an oft-told story form her talk show days, Oprah Winfrey recalls inviting a group of skinheads to her talk show.

Her goal was to expose that the ugliness of racism and bigotry didn’t die with the passage of the Civil Rights Act. While her intentions may have been pure, the skinheads (unsurprisingly) got belligerent, and Oprah instantly realized her error.

Aside from the obvious optics (the most powerful Black woman in media giving a platform to White racists), she realized that what had been a mostly fringe group the day before was now front and center on the #1 daytime talk show on television.

Oprah realized while millions of viewers were probably watching in disgust, she was also broadcasting the skinheads’ message to people who agreed with some (or all) of their rhetoric.

Oprah’s story is a very extreme example of a lesson that stans have yet to grasp: it is counterproductive to try to shame people by giving them the attention they wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. And while stans love to position themselves as protectors of their faves, more often than not, they attract even more negativity towards them.

Example:

Let’s say you have a random, irrelevant Twitter troll.

- This account follows 648 people, but only 12 follow them back because they are just as insufferable and unlikable under the cloak of Twitter anonymity as they are in real life.

- This account probably tweets radicalized messages like “EAT THE RICH.”, but the person behind the account orders their Starbucks exclusively through their iPhone app because they’re too afraid to make eye contact with the cashier.

- There’s an 85% chance that this account has an anime or cartoon avatar.

“Irrelevant Twitter Troll” tweets something like:

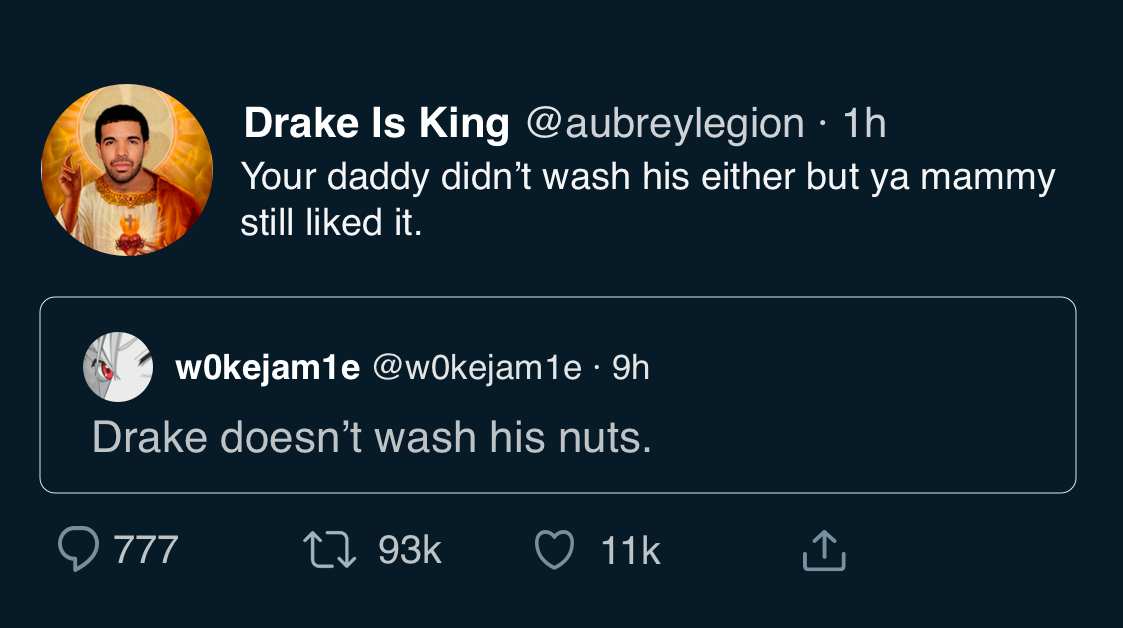

Now let’s say you have a Drake stan account (AubreyLegion).

- This is Drake’s biggest stan account.

- This account has over 600k followers (including Drake).

Because their account revolves around how liked and popular Drake is at this very moment, this account spends all day searching Drake’s name looking for anyone who says anything negative about Aubreysus so that they can drag them.

Stan Account finds the tweet from “Irrelevant Twitter Troll” and quote tweets it:

What was initially seen by 12 people (at best), has now been retweeted by nearly 100,000 people.

Now let’s say you have a freelance culture writer who has built a career off of stealing content from Black Twitter, Black Gay Twitter, and Stan Twitter.

Culture Writer sees the tweet by AubreyLegion and now feels compelled to pitch a piece about it. Then Culture Writer gets underpaid by a wealthy media company and the piece gets published.

Now, when you search Drake’s name on Google, here’s the first thing you see:

And because we don’t read articles as much we scan headlines, “Drake Doesn’t Wash His Nuts” becomes the #1 trending topic on Twitter and the Drake stan account is angry because of a story they help spread.

It’s the Stan Twitter Circle of Life:

What would have died in the abyss of Twitter irrelevance now becomes a viral news story all because:

- Stans have convinced themselves the best way to fight negativity towards their fave is to spread it to thousands of people who probably wouldn’t have seen it otherwise.

- Stans know that any backlash that occurs will be directed towards their faves rather than to anonymous Twitter accounts

- Some stans are willing to get engagement by any means necessary, even it means getting their fave dragged.

“I’m a fan, I can’t possibly be part of the problem.”

“I have the right to critique to my fave…right?”

The main problem with most stans critiquing their faves is that it’s never reciprocal.

You could be hiding behind an avatar of Ariana Grande, on stan account with thousands of followers because of Ariana Grande while simultaneously dragging Ariana Grande and she couldn’t possibly drag you back because your entire online presence is devoted to her. It’s easy to be critical when you’re hiding behind someone else’s life and have no actual skin in the game. Stans often amass thousands of followers off of an artist’s name and then decide (for likes, laughs, or retweets) to throw that artist under the bus.

“But I’m a true fan. I’ve bought albums and concert tickets. I have the right to behave however I wish.”

Let’s put this in more understandable terms.

Let’s say one of your two OnlyFans subscribers sends you a $3 tip. And because of that tip, they create an imaginary relationship with you and assumes a level of overfamiliarity with you that borders on obsession. You’d probably treat them like the weirdos that they are. And yet, so many stans feel that because they may actively support their faves and have created relationships in their head, any toxic behavior they exhibit is not only excusable but endearing.

Even good-intentioned stans who have been fans for years have a hard time with the idea that they can be both supportive and demoralizing at the same time.

How To Deal With Toxic Stans

It’s hard to pinpoint an effective solution for toxic stans, especially toxic stans who don’t know they’re toxic.

Many people believe that it’s the artist’s responsibility to rein their fans in; however, when dealing with stans, artists are often placed in no-win situations.

Few artists want to publicly chastise fans who support them, even if those fans are “supporting” them in harmful ways. And although some artists may want to drag annoying fans, artists may find that the best responses is no response at all. Many stans are proud of being obnoxious, and because they feed off any attention (good or bad), their fave telling them to calm their collective bussy would only rile them up more.

Realistically, there aren’t any quick and clean fixes for the evils of stan culture. I’m not saying that all stans should be rounded up, horsewhipped, and banished to an island with no access to Chart Data or Twitter. But perhaps the end of stan toxicity ultimately comes when stans start to demand the same decency from each other as they do from non-stans.